Having good conversations

I went into this episode thinking it would be another checklist on how to be “more charismatic” or “win friends and influence people without becoming insufferable” because of the bait catching title "Why People Don’t Like You", but.. it wasn’t that. It felt more like an episode that peeked into Steven Bartlett's struggle with social gatherings and how he identified himself as an introvert. It was also an episode where I felt more acutely the struggles of men in the social space and mental wellbeing.

Alison Wood Brooks—Harvard professor, behavioural scientist, and author of Talk—basically dismantled the idea that good conversations are about personality. Or charm. Or being interesting. Her passion in conversations arised from her upbringing - her being an identical twin in a small town next to lake and having the opportunity to observe her twin fail and success in many different social scenarios. Her research is primarily in social anxiety.

Conversations are about effort. And most of us are bad at that. This episode was also about understanding why conversations fail quietly, awkwardly, and repeatedly—and why we keep blaming ourselves instead of the mechanics underneath.

Conversations may not be natural

We like to think conversations are natural. You either “have it” or you don’t. Some people are just social. Others are introverts who “hate small talk.”

Alison’s work basically says: That’s nonsense!

Conversation is one of the most cognitively demanding things humans do. You are tracking tone, words, facial expressions, timing, hierarchy, emotion, memory, social norms—all in real time. And we expect ourselves to do it flawlessly without training. Remember that good old saying that you need 10,000 hours before mastery? If you think you are a master at conversing without spending 10,000 hours, it would be nice asking a toddler to play Chopin right at the get go.

No wonder people feel anxious. No wonder they over talk. No wonder they leave interactions replaying everything they said like a crime scene investigation. As a result, people want to relieve that feeling by making concessions or exit the interaction.

Over here, I felt that Steven Bartlett was being genuine when he admitted that his happy state is being alone (note this man can be rather unaffected in some episodes). Given his success, I expected him to be more outgoing, perhaps even a social butterfly. So him admitting his vulnerability felt refreshing and authentic. He even set himself up as being happy alone felt like having a weak trait. Alison reframes that not as a weakness, but a preference. Introversion isn’t a defect. Avoiding shallow interactions doesn’t mean you are antisocial—it may just mean you crave depth and control.

And that idea of control matters more than we admit. I wish Alison expanded more on this topic but it moved on quickly.

Anxiety Isn’t the Enemy (Trying to Calm Down Is)

One of Alison’s most unintuitive findings: telling yourself to calm down does not work.

When people feel anxious—before a presentation, a negotiation, or a conversation—they try to suppress it. That backfires. Instead, reframing anxiety as excitement actually improves performance.

People who told themselves “I am excited” performed better than those who said “I am anxious.” Same singing task. Same nerves. Better outcome.

This applies to conversations too. Social anxiety isn’t solved by retreating, apologising excessively, or exiting early. That’s relief-seeking behaviour. It protects you short-term and damages connection long-term.

Which explains a lot about why polite, agreeable people are often forgotten.

On the other side, we are introduced to the term BATNA - Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement. An example of a job offer is given. You are best served when you already have a better offer elsewhere. Then, negotiate by asing the right questions - are you talking to the right person? Does the company have funds? How can I justify a way that's compelling to the hiring managers? They need to want to keep you.

It was somewhat distracting that the conclusion on the negotiation example was to simply focus on doing things that add value; and good things will follow. Find our what your organisation or boss needs, deliver that consistently, and your salary will go up in this cycle. This is a theory we have seen in many other podcasts.

Conversations Aren’t One Thing — They Are Four

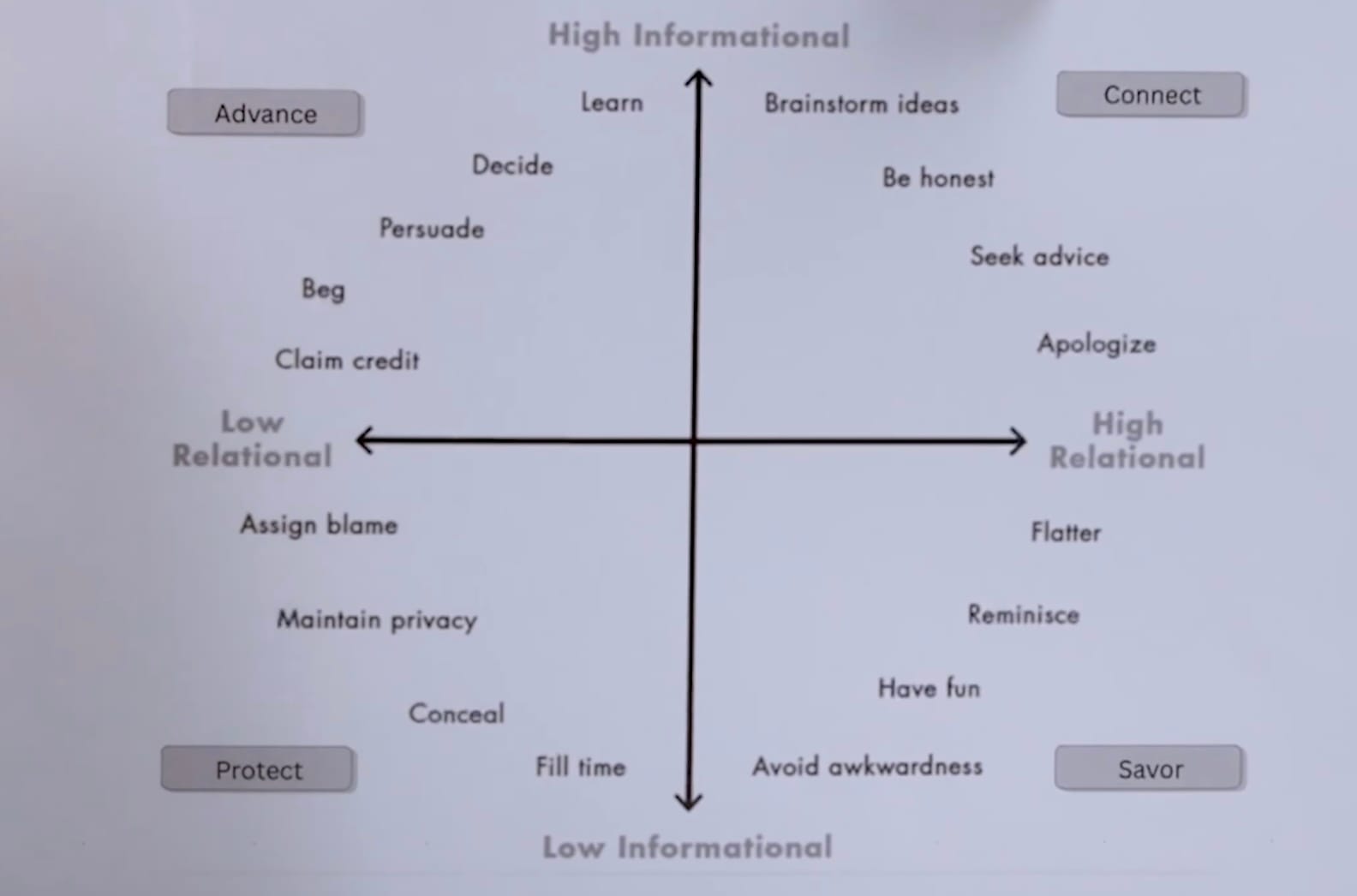

Alison breaks conversations into four modes:

- Advance – High information, low warmth (giving instructions, debating, correcting)

- Connect – High information, high warmth (the sweet spot)

- Savor – High warmth, low information (bonding, reminiscing)

- Protect – Low information, low warmth (supporting, comforting, holding space)

Most people think “good conversation” means Connect all the time. That’s impossible. Some moments require Protect. Others need Advance. Problems arise when people mismatch modes—when one person wants to connect and the other wants to advance, or when someone needs protection and gets logic instead.

This alone explains half of relationship conflicts.

The Apology Trap

Here’s another uncomfortable truth: over-apologising makes things worse. Most apologies fail because they rehash the mistake instead of resolving it. The most effective apologies do three things:

- Take ownership

- Make a concrete promise to change

- Move forward

Apologising more than twice in a conversation becomes a reminder, not repair.

This pattern holds even in extreme settings—like prison rehabilitation programs. Future-oriented accountability beats emotional self-flagellation.

Good to know. Painful to realise. Practising this takes many tries before an apology will sound sincere. The good news is, you can only practise until it gets better. I personally don't think practising apologising will get worse over time.

Why Disagreement Kills Conversations

When we disagree, a different part of the brain lights up. Literally and science backed.

Once that happens, curiosity shuts down. Listening becomes harder. The conversation narrows. That’s why Alison’s “magic phrase” works so well:

It makes sense that you feel X about Y.

You are not agreeing. You are validating reality. It feels patronising on paper. In practice, it keeps the conversation alive.

Follow it with:

Tell me more.

Most people just want to feel understood before they are corrected—if they want correction at all.

The TALK Framework (Simple, Not Easy)

Alison’s framework for better conversations:

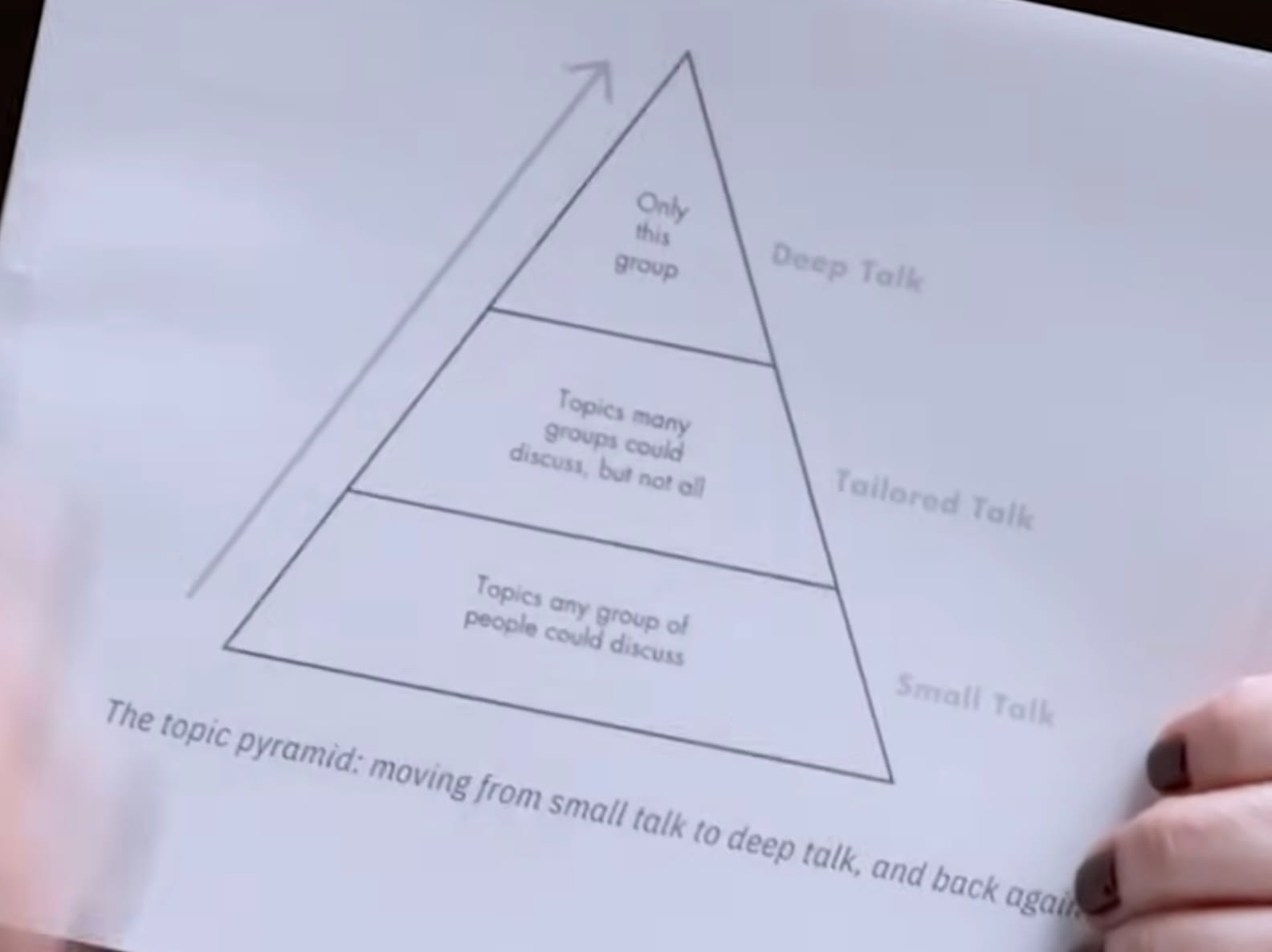

- Topics – Choose wisely. Don’t live in small talk forever, but don’t parachute into deep talk either. One idea is to prepare before conversations. This prep time could be as little as 10-30 seconds, or it could be much longer. Most people take the mistake of staying at small talk too long.

- Asking – Questions matter. Men ask fewer than women. Another fun fact, men are also more likely to agree to go on a second date.“Yeah yeah yeah” is not listening. Also, don't ask questions end up being about yourself. Be genuine interested in the person you are talking to. Be present.

- Levity – Lightness in conversations. Warmth beats seriousness. The more common enemy of conversations is actually boredom and disengagement. Our minds are distracted at least 25% of the time in a conversation. Callbacks signal attention and memory. "Remember what you told me last summer?" Levity is also about doing a light switch to have a bit of fun, then back again to the main topic.

- Kindness – Energy matters. Names matter. Respect matters. Using respectful language is associated with less conflicts. If you are having less or no energy that day, you will be less kind because remember, conversations takes effort. Being kind is different from being liked. Likability should be distanced, its a very narrow goal of conversations.

None of this is revolutionary. That’s the point. People who over talk tend to be less respected. Steven draws some insights here which I found quite intriguing. He talks about the contribution score of a person, which is based on their historical airtime. High score = people will listen to you. Low score = people pre-dismiss you. Ouch!

Low contribution score people is about egocentrism. We all know that someone who is bad at following a topic in a group conversation. They tend to say something completely unrelated, especially when they cannot not talk.

The barrier isn’t knowledge. It’s attention and in my opinion, self- and situational-awareness. Human beings are terrible at guessing other's people perspective using our own perceptual realities. The only way to know is to ask.

Ask lots of questions. Be intrigued. Be interested. Be curious. Entrepreneurs fall into this trap a lot. They are super excited to share their product which they find to be the most interesting thing in the world - but we all know this is not the same for everyone. We all have that partner that has zero interest in cars or in embroidery or in the latest fashion. Entrepreneurs have to learn to ask questions. Find a topic that both parties are interested in and then go deep into that topic.

Men, Loneliness, and the Sideways Conversation Problem

One of the darker parts of the episode: male loneliness.

Men tend to talk side-by-side. Activities. Narration. Status updates. Less vulnerability. Women talk face-to-face. Hopes. Dreams. Emotional processing.

The data is grim: a significant percentage of men report having zero close friends. Alison thinks some 40% of men don't have any close friends while a quick google pulled up 15%. Men with close friends have dropped by some 30-40% since 1990s.

This isn’t a personality flaw. It’s a conversational skill gap. A typical men's conversation would be like narrating their lives and what's happening around them. Men tend not to have deeper, vulnerable conversations.

Good question to start could be

What are you excited about lately?

Or

What have you been struggling with recently?

Now of course, I would say it takes some common sense and situational awareness to use those questions in appropriate circumstances. Don't go asking a happy mum that's smiling widely what she has been struggling with!

Men have come to rely solely on their romantic partner for emotional support. Women have their friends to support. As a male, I too find it really hard to have a deep conversation. I would default to 'its not in our nature', but here I remind myself.. conversation takes effort! 'TALK' and the four modes of a chat...

Then we still have non-verbal and verbal cues. Non-verbal cues are normative. Leaning forward, smiling, nodding quietly, signifies interest and attention in certain cultures. Verbal cues like validating, affirming, paraphrasing, asking follow-up questions... gosh! There's so much work in a conversation, which brings us to..

Augmented communications with AI and our digital age

Here Alison shared an experiment that she did recently with her class. Office hours with an AI version of herself. She was pleasantly surprised by the outcome. To summarise, pros: ChatBots are always available, not judgemental (not grading you and having a social status difference like teacher and student), and always have the bandwidth to craft feedback. Cons: sort of brings everything into the mean, flattens personality, less creativity.

I want to add another con to AI therapy - silence. Bots are never silent. They always reply. But I think sometimes silences can mean a lot. There is much information in a shared glance. Longer pauses are a sign that you are comfortable in a longer term relationship. So if we cannot get AI, how about our many forms of communications now?

Digital communication creates fragmented attention. Think about the ways you can now be connected than in the past. Emails, phone number, WhatsApp, FaceTime, DMs, advertisements, micro transactions, the ton of notifications that pop up on our phones... We are always “reachable” but rarely present. Text strips context. Devices interrupt. Conversations get replaced, not augmented.

Real connection remains effortful. And irreplaceable. Put that phone away from the table. Now! (Unless you don't really want to talk, that I understand).

The Real Takeaway

This episode wasn’t about being liked.

It was about showing up with intention.

Conversation isn’t self-expression. It’s co-creation. Listening isn’t passive. It’s work. Over here, the duo discusses authenticity, i.e. do you show up at work everyday being your absolute true self? The answer is strictly no.

Authenticity isn’t blurting everything—it’s aligning values with context. Bring the values that make you work well. Adjust your behaviour to fit the needs of the situation. Not pretending and acting are different things. For more depth, Alison recommends reading 'Strategic Authenticity' by Juliana Pillmer. Steven has another spark here:

Moments of insincerity in pursuit of sincerity

If conversations keep failing, it’s probably not because you are boring or broken. It’s because no one ever taught you how this actually works. And now you know.

Whether you practice it… that’s another conversation entirely. Also, since this episode lands right before Christmas, where there's usually a lot of social gatherings... Isn't it the best time to start practising?

Source | DOAC - Top Harvard Professor: The Psychology Of Why People Don't Like You!